By Dr. Kate Placzek, ZRT Laboratory.

I was in teenage hell. Overnight, I went from being completely oblivious to what I looked like, to being obsessed with my appearance. And let me tell you, I did not like what I saw in the mirror. Too tall and too skinny, with an awkward toothy grin, uncoordinated and gangly, and I didn’t seem to know where my limbs were supposed to be around me. I wanted pretty hair and a semblance of curves, like many of my friends; instead I was a bean pole with a grease mop on my head. I wanted clear glowing skin; instead I was covered in acne. I felt miserable. I detested being a teenager. Thanks, puberty!

I had to deal with acne for the duration of middle school, high school and college. During that time, at all times, there was a crop rotation of pimples in various stages of sprouting development in plain sight. I spent hours obsessively picking at my face in the mirror, or mindlessly digging at those under-the-skin painful cysts while doing homework. Many nights I showered my pillow with tears of frustration and dread over getting up in the morning and showing up to class with the damage from the night before glaring on my face. And nothing really helped make it better. My mom and her friends, bathing in confidence from having skin worthy of a Neutrogena commercial, would shake their heads empathetically at me in disbelief ascribing it to my changing hormones: “don’t worry,” they would say “it will get better.” “When?” I would sigh back. But they would avert their eyes without a good answer on hand. All the while I carried a sense of doom and shame over not being able to control my seemingly raging hormones that wreaked havoc on my face.

Acne & “the Pill” – a Complicated Relationship

My terrible acne situation didn’t improve until graduate school when I finally decided to take birth control pills for this specific reason. And it helped my skin clear up tremendously (but resulted in a slew of other undesirable side effects that I will address in a different blog post). So I walked around, blissfully happy about having clear skin for the first time in my life, working on my confidence of looking more like a grown woman than a gawky teenager, with all of my hormones effectively suppressed. Fast forward a few years from receiving my PhD when my husband and I decided we were ready to start a family, and I stopped taking my birth control pills. By that point, I had already forgotten about the emotional damage that acne had caused me. Much to my dismay, it came back with a vengeance. When I went off “the pill,” almost instantly I developed a full-on zit beard that spread all the way along my chin to my ears and down my neck (apparently this is a very common pattern in females [2]).

Skin is an Endocrine Organ

As I sit here diligently recalling and writing about my frustrating acne history, I contemplate the complexity and the deep beauty of skin, an organ with its own plethora of endocrine commitments. Specifically, because skin is a tireless endocrine organ; our hormones play a major role in its healthful and youthful appearance. Women are all too familiar that as they age and estrogen levels decline towards menopause, skin loses elasticity, leaving them prone to developing wrinkles. What about acne? Were my mom and her friends right about hormonal shifts giving rise to my ever-so-frustrating adolescence? The short answer is – yes, they were right! The long answer is somewhat more complicated. So, I’m going to try and break it down into digestible parts.

What is Acne? And What Makes it so Terrible?

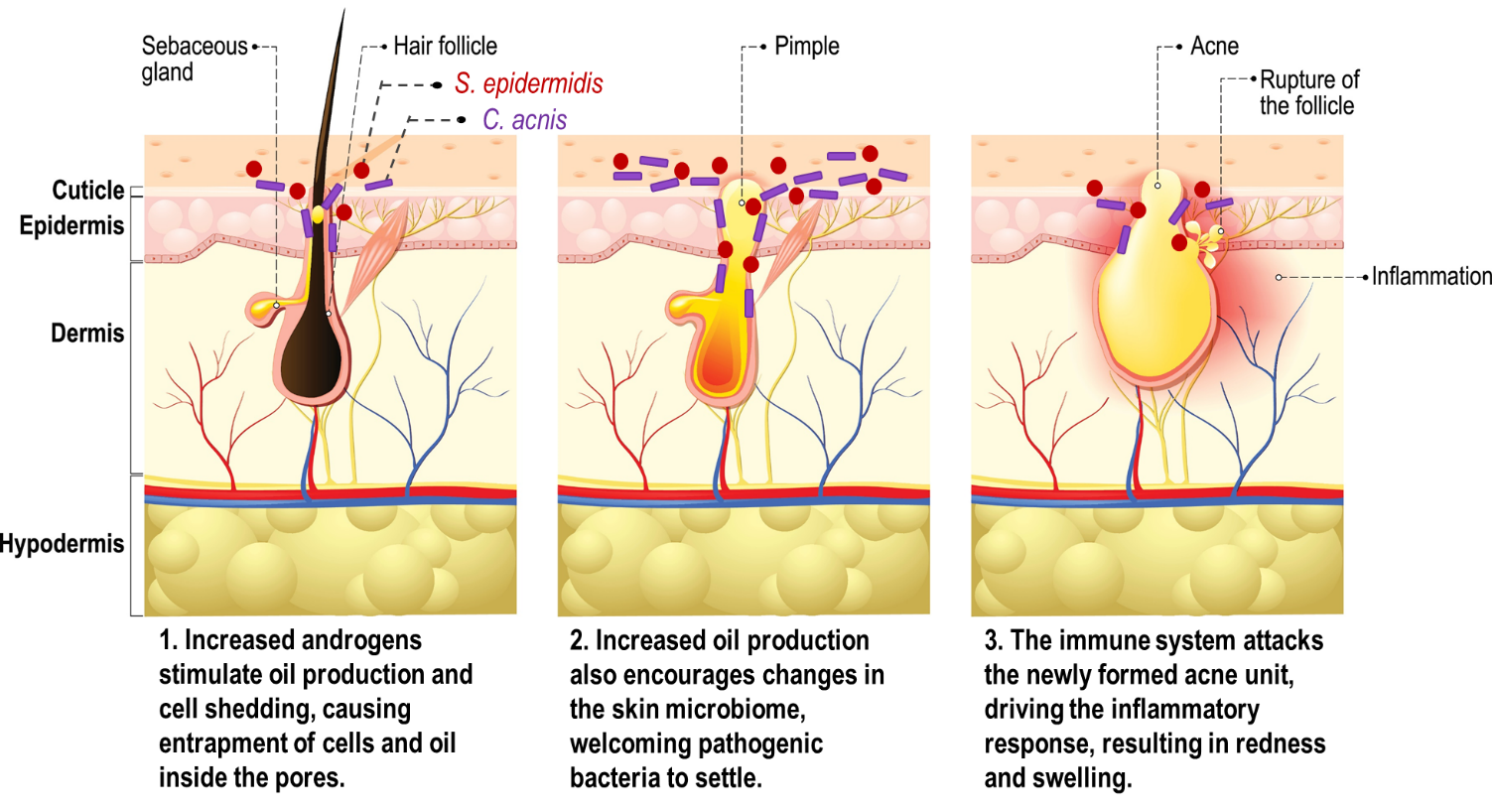

Acne (medical name “acne vulgaris”) is an inflammatory condition (or a disease of the pilosebaceous unit if you ask a Dermatologist [2]), where the balance among the skin microbiome, hormones, and a proper inflammatory response is lost. The hair follicles on the skin basically become clogged with dead cells and oil from the skin – a medium so rich and fertile that a variety of bacteria claim it as their bed and breakfast. This results in pimples or bumps that heal ever so slowly, and when one seems to start going away, the others crop up. The factors driving this process are multifactorial, and in the majority of cases include:

- Increased androgens, or “androgen dominance” (in puberty, adolescence, right before a period, or in perimenopause) trigger an increase in oil (sebum) production and stimulate abnormally rapid shedding of skin cells and subsequent entrapment of the oil and the dead cells inside the pores. This also leads to an enlargement of the sebaceous gland. Note that even when androgen levels are normal, with low estradiol and progesterone, androgens can appear “elevated” in a functional sense, giving rise to acne

- Skin microbiome changes that “help” with colonization and proliferation of the duct with pathogenic bacteria

- The immune system, always in vigilant surveillance mode, detects the newly formed acne unit and attacks it, resulting in inflammation, redness, swelling and pus-like fluid buildup

Fig. 1 Overview of the skin pilosebaceous unit, the bacterial population within it, and acne formation. Adapted from [1].

Let’s Talk About Androgens

Androgens (e.g., Testosterone (T) and dihydrotestosterone (DHT), the more potent metabolite of T), are historically pegged as intrinsically “male.” Men have about 10-times more T than women. While women have less T, they also have and need androgens to maintain a sense of well-being, elevate mood, improve libido, see a decent response to exercise, and give rise to estrogens. Androgens also play a role in regulating normal dermal physiology, via their actions on the androgen receptors, expressed at the surface of our skin [3].

An imbalance in androgen metabolism and levels can set forth a series of events that inadvertently end up presenting on our face as acne. Because the skin is highly expressive in androgen receptors, persistent activation of these receptors with high levels of androgens in the sebaceous glands results in a dramatically revved up output of sebum. Both testosterone and DHT can bind to the androgen receptors in the skin; however, DHT is much more potent. Research suggests that elevated androgens in puberty initiate acne symptoms, especially in girls, and accompany the persistent progression of acne into adulthood [4, 5]. So, in a sense, high androgens in puberty can prime androgen receptors to be more sensitive to even normal androgen levels later in life [6]. Estrogens and progesterone also play a role in how androgens affect the skin. They are both anti-androgenic and account for the pregnancy glow in the skin and hair when estradiol, estriol, and progesterone levels skyrocket to very high levels and androgens decrease, or at least don’t increase.

The strong androgen-acne connection is especially evident in disorders like polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), in which acne, scalp hair loss and increased facial and body hair are common [7]. Other disorders, such as congenital adrenal hyperplasia or CAH can present with similar symptoms to PCOS. Saliva LC-MS/MS testing can help differentiate between the two disorders. Additionally, hyperprolactinemia is another common disorder that leads to PCOS/CAH-type acne symptoms, easily missed if not looking for it specifically, and ZRT’s serum test covers that territory.

A simple saliva test can assess the levels of bioavailable androgens (DHEA and testosterone) and a dried urine test can assess DHT levels to see if abnormal androgen metabolism is to blame. Anti-androgen therapies have now been developed to help manage androgen-triggered acne [8].

When it Comes to Skin Health, Does Food Matter?

In addition to hormonal imbalances, diet plays a big role in the development and propagation of acne. The Western diet, which is characterized by a high intake of hyperglycemic carbohydrates and dairy products, increases insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1). Together, through a series of biochemical events, they drive androgen levels higher and thus promote more oil production and induce inflammation [9].

Diet doesn’t just induce changes in the housekeeping molecules that regulate glucose – diet also shapes the gut microbiota, which can then influence skin microbiota. Research suggests that a low fiber/high saturated fat Western diet causes fundamental changes in the intestinal microbiota, producing metabolic and inflammatory skin conditions [10].

Dietary modifications aimed at reducing high glycemic index carbohydrates, dairy protein, and saturated fat and the introduction of sea fish, green tea, resveratrol and vitamin D-rich foods may help attenuate acne [9].

What Role Does Our Microbiome Play in Our Acne?

Our skin is a rich ecosystem, inhabited by billions of diverse microorganisms. Most of the time, there is a healthy and concerted balance between our skin and the microorganisms living on it. However, if skin conditions are permissive, pathogenic bacteria can attach and proliferate, forming entire colonies. Skin oil (sebum) is a major influential factor in controlling microbial diversity at the skin level. In sebum-rich areas lipophilic bacteria are more dominant and drier skin may promote a more diverse microbiome. Therefore, skin that is more oily is more likely to experience a switch from commensal to pathogenic bacterial populations, resulting in acne and its accompanying inflammatory response (redness and swelling) – clinical signs of imbalance between our skin and the microbiota [9]. Some authors present preliminary evidence that certain probiotic species can also help control the population of pathogenic skin bacteria [1].

Perhaps my hormones aren’t as revved up as they used to be when I was thirteen, and that’s what has helped my face clear up; or perhaps I’ve cleaned up my diet enough to see a difference on my face – the point is that there is a reason behind acne pathology, and today there are many resources available to help understand what is driving this irritating condition for each individual patient. Additionally, treating your skin with love and consideration may ease the anxiety over having acne. Now that I am in my late thirties, I am finally beginning to view my skin as a friend and not a foe. I am careful to recognize patterns when certain products or activities make my skin break out, and subsequently treat it with gentleness and care; appreciating every bit of it, even the patches with scars from previous battles.

ZRT Laboratory’s saliva and dried urine testing can help you determine if your androgen levels are out of balance and a possible cause of your uncontrollable acne. Order your next test today to find your way back to clear skin.

Relevant Tests

References

- Lee, Y.B., E.J. Byun, and H.S. Kim, Potential Role of the Microbiome in Acne: A Comprehensive Review. J Clin Med, 2019. 8(7).

- Tan, A.U., B.J. Schlosser, and A.S. Paller, A review of diagnosis and treatment of acne in adult female patients. Int J Womens Dermatol, 2018. 4(2): p. 56-71.

- Lai, J.J., et al., The role of androgen and androgen receptor in skin-related disorders. Arch Dermatol Res, 2012. 304(7): p. 499-510.

- Williams, C. and A.M. Layton, Persistent acne in women : implications for the patient and for therapy. Am J Clin Dermatol, 2006. 7(5): p. 281-90.

- Preneau, S. and B. Dreno, Female acne - a different subtype of teenager acne? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2012. 26(3): p. 277-82.

- Kim, M.H., et al., Integrated targeted serum metabolomic profile and its association with gender, age, disease severity, and pattern identification in acne. PLoS One, 2020. 15(1): p. e0228074.

- Gersh, F., PCOS SOS. A Gynecologist's Lifeline To Naturally Restore Your Rhythms, Hormones, and Happiness. 2018: Integrative Medical Group of Irvine.

- Dreno, B., Treatment of adult female acne: a new challenge. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2015. 29 Suppl 5: p. 14-9.

- Melnik, B.C., Acne vulgaris: The metabolic syndrome of the pilosebaceous follicle. Clin Dermatol, 2018. 36(1): p. 29-40.

- Bowe, W., N.B. Patel, and A.C. Logan, Acne vulgaris, probiotics and the gut-brain-skin axis: from anecdote to translational medicine. Benef Microbes, 2014. 5(2): p. 185-99.